I am honored and humbled to join SDI as the new editorial director. Part of that role is to be editor of Presence Journal and Connections. In this issue of Connections, we’re highlighting some pieces from the last handful of years. One is from Rev. Rich Nelson, a 2019 New Contemplative. He shares a sentiment I could have expressed myself word for word: “I sensed that I had found my tribe, my community for this next part of my journey … here sits a table of people who are committed to an authentic, inclusive, respectful and loving way of being in the world.”

We are in the midst of a period of at least instability if not major realignment—which as Karen Armstrong, Phyllis Tickle and others have pointed out happens from time to time. While many assume Gen-Y and Z seekers’ open-minded exploration and resistance to dualistic absolutes reflects a flakiness or non-seriousness, it fills me with hope. What I see is an active engagement with sense-making in a world that offers far too little of it. It may not always be fun to live in interesting times, but it can be rich and fulfilling. We spiritual directors and companions have an important role to play in walking with those seekers made homeless by these tectonic shifts. And with all who feel less sure on their feet because of them. We do this through what Bayo Akomolafe calls sanctuary—not a place with solutions, but a place for integration, for perspective. And I love how Bayo describes “allowing our children to guide us to the edges of lakes.” All those engaged in practices that involve active listening, holding space and opening to new perspectives are contributing to this holy work.

Phil Fox Rose

Editorial Director, SDI

The Missing Revolution

By Rev. Rich Nelson

Something is missing and we all sense it.

Some of us know it consciously, we see it is missing, we name it, we mourn that it is not there.

Some of us know it intuitively, we sense that something’s missing but putting words to it is much harder for us.

And some of us only know it is missing unconsciously, and the missing of it manifests in our lives all kinds of, often unhealthy, ways.

But something is clearly missing and, in one way or another, we all know it.

In the past century, we have seen more change than nearly all of human history combined. I know people who picked cotton in fields as children, lived in houses without plumbing or electricity, whose primary mode of transportation was foot or horseback, and attended school in a one room building where the teacher was also the pastor of the local church. Life as such had much more in common with people who were born 3,000 years before them than it does with people who are born today. It was a simple life, a dangerous life, a hard life, but there was also much beauty and goodness in it.

In the past century, we have seen the industrial revolution transform the way we work, the technology revolution transform the way we communicate, the medical revolution transform the way we treat illness, the scientific revolution transform the way we understand the universe and the social revolution transform our concept of family. In the course of 100 years, we went from sharecroppers to space travelers, from having no phone to instant video calls around the globe, from common disease as death sentence to the decoding of DNA, from a Newtonian world to quantum physics, and from puritanical pietism to gay marriage. There is much to celebrate in each one of these revolutions and the many changes associated with them.

And still, something crucial is missing. And we all can feel it.

Especially now. Under the rally cry of protectionism and isolationism, an old, fear-based way of being has dug in its heels and reasserted itself with shocking force and cruelty. This old way of being asserts that some people are superior to others, that anything “other” is to be feared, that some people are more blessed than others by God, and that some ways of seeing and believing are not only invalid pathways to the divine but inherently evil.

Yet, in the face of all the hatred this old order contains, there is a new revolution in the waiting. And whether or not it is manifested into reality depends on you and me.

Alongside all these other major shifts in the way we live and conceive of life, the religious revolution has yet to come. For we continue to gather, to believe, and to self-identify in ways that still bear striking resemblance to the tribal religions of thousands of years ago.

There is much beauty and goodness in this way of life. As an Episcopal priest, I stand in awe each time I place the chasuble over my head prior to celebrating holy communion, remembering how it connects me to a young Middle Eastern boy named Samuel who wore a simple linen ephod as he served under the priest Eli millennia ago. As the veil is lifted off the elements on the altar, I am reminded of the curtain in the Temple and how my own faith tradition teaches that the simplest of things are among the holiest, that God can be present in a piece of bread or a drop of wine. The details may be different for you and for me, but our connections to the ancestors of our various faith traditions is something deep, and rich, and good.

But the way we organize ourselves around these deep truths is archaic and in desperate need of rethinking. We need religion that is re-imagined and revolutionized. We continue largely to gather only with those who think like us, who look like us, who increasingly are the same age as us, who adhere to our own narrow understandings of the divine, and thereby cut ourselves off from the rich tapestry of humanity and all the gifts that our differences hold for one another. This division exists not only between religions but within each of them as well. I feel I have entirely more in common with an enlightened Buddhist monk or a loving Muslim mystic than I do with certain arrogant and intransigent Christians.

I seek to live with and learn from those who are different from me in practice and even in faith, but who are my sisters and brothers in spirit.

This year, I was chosen by Spiritual Directors International as one of the “New Contemplatives” for 2019. One of the things this has allowed me to do a few times now is get on a monthly video conference with ten other New Contemplatives and our coordinator, Lizzie Salsich, and just begin to share something about who we are and our spiritual journeys. We are very diverse. We come from different places and different races. We have different ways of engaging our spirituality, and different ways of thinking about guiding others in their own spiritual journey and faith practices. However, there is, at least for me and I hope for them, a palpable sense of deep goodness, blessedness, and kinship in the time we spend together.

What does it say that I, a white, straight Christian man who lives in Texas and wears cowboy boots, feels more in tune with a reiki practitioner, an African American womanist, a Filipino beekeeper, a Latina social worker, a spiritual geneticist, a New York shaman, the first blind, female rabbi, and a black, queer trans man than I do with many in my own tradition?

I think it means our understanding needs updated when it comes to what makes an effective form of religious expression.

As we recently listened to Rev. SeiFu Anil Singh- Molares, the Executive Director of SDI, describe a vision for this organization that is both connected with the depths of our tradition as spiritual directors but also increasingly defined by the breadth of our very diverse spiritual expressions, I sensed that I had found my tribe, my community for this next part of my journey. I’m relatively new to SDI and I’m sure that, like any other human gathering, it is full of challenges. But at least here sits a table of people who are committed to an authentic, inclusive, respectful, and loving way of being in the world. If that’s my new “church,” I welcome it.

The religious revolution is yet to come. But when it comes (must we still wonder if it comes?), it will change our way of life as surely as any of the other revolutions we’ve witnessed over the last century. As we continue to identify the commonalities of our faith expressions and celebrate them while also acknowledging our differences, and feeling blessed by those as well, we will form a new community and show others how to do the same.

This is the revolution our world still awaits. It is our responsibility and profound honor to be the ones to help usher it in. Let us not delay.

Originally published in the February 2019 Vol. 28.1 issue of Connections.

Rev. Rich Nelson

Rev. Rich Nelson is a spiritual director, writer, and the creator and guide of the emerging global following The Way faith community. You can connect with him and learn more at followingtheway.me and revrichnelson.com.

Spiritual Companionship as Sanctuary

By Bayo Akomolafe

Sanctuaries are not places where we are set straight; sanctuaries are places where we are broken down. Sanctuaries are not sites of solutions. They are practices that help us see that the way we see the problem we want to address is often part of the problem. Sanctuaries are not committed to reinforcing rectitude, as much as they are invested in touching inclinations and the intersectionalities of our bodies. Most importantly, sanctuaries are assemblages or reconfigurations of the dynamic cross-cutting relationships between us and our children, us and our ancestors, and us and the other-than-human agencies in and around us.

I cannot help but think of spiritual companionship today as the strategies described and embraced in the concept of sanctuary. Not just guidance but actively losing our way in order to be found anew. Allowing our children to guide us to the edges of lakes where sticks and ducks and lichens and trees and soft wind and rock and worm produce alchemical magic. And not just an inexorable march into the future but an active practice of re-membering the past as the haunting temporality folded into the density of the present. Spiritual companionship is not a private affair of seeking redemption and meaning; it is a public endeavour that connects us to a more-than- human tapestry that includes sense and non-sense. The individual has never been alone. The individual is a teeming community of others …The task of spiritual companionship is dwelling-together-with and losing our forms generously in order to find other ways of with-nessing a troubled world.”

Originally published in the November 2019 Vol. 28.4 issue of Connections, this is an excerpt from the keynote address Bayo gave at the 2019 SDI conference in Bellevue, Washington. You can watch the whole speech here on SDI’s YouTube Channel.

Bayo Akomolafe, PhD

Bayo Akomolafe, PhD, is a father, husband, diaper changer and lover of words and rich conversations. An author, speaker, public intellectual and teacher, Bayo also serves as Chief Curator of The Emergence Network – an organization that is committed to unsettling habitual modes of perception and practitioner engagements around challenges and issues of our time. practices that might help us live well in the ruins of modernity.

Thirst and Compassion

By Busshõ Lahn

How sad that people ignore the near and search for truth afar:

Like someone in the midst of water crying out in thirst,

Like a child of a wealthy home wandering among the poor.

—Hakuin Ekaku, 1686-1769, from “The Song of Zazen”

The famous Japanese Zen master Hakuin Ekaku starts a crucial verse of one of his famous teaching poems with the two words, How sad.

Sadness. Yes. The state of the world, the state of the human heart so much of the time; especially now in the time of Coronavirus, the resurgence of fascism, and the climate emergency. Sadness. Grief. A defining experience of human life.

Our emotional response to his image of the thirsty person is compassion for their suffering, then a longing that they find the wisdom that helps them see that they are surrounded by what they need. The universal metaphor of thirst seems perfectly offered to create compassion and wisdom in the mind and heart of the reader (i.e, we all know thirst, and we can all see the tragedy of being thirsty while surrounded by water).

It’s important that we understand these qualities and the order in which they most helpfully arise. Compassion first. Wisdom second. We skip sadness at our peril. Without compassion, wisdom is a cold examining room table, a ruthless law, a reckless sword. Explain to a crying baby precisely why it’s uncomfortable or explain to a feral cat why she needn’t fear you and should take the food from your hand.

Right?

So, wisdom without compassion isn’t really wisdom. It’s dry soup mix in a waterless desert, it’s an empty house, a legal arrangement made between no one and no one. Of course, compassion without wisdom isn’t compassion anymore; it’s codependency, enmeshment, and enabling.

But what I see most often, especially in spiritual circles, is people rushing to get to the wisdom bit, and ignoring or skipping over the compassion bit.

And of course, they do. Compassion hurts, and we don’t like to hurt. In fact, most of us drawn to a disciplined spiritual path are doing it- consciously or unconsciously – to get away from the pain of our lives. We want enlightenment because we imagine it’s a place filled with love that never hurts, a perfect wave that crests… but never breaks.

And here is the water metaphor again, the metaphor for our truest nature, being used to describe that which we are and that which surrounds us, yet that which we thirst for. “In the midst of water, crying out in thirst.”

This is a bleak image, and one I think we can all relate to.

“Water, water everywhere, and not a drop to drink” is the old sailor’s line, about being at sea without drinking water. We cannot live on saltwater, yet that’s what was all around. The irony of dying of thirst while floating on trillions of gallons of water.

The likening of the spiritual impulse to thirst is one that touches me deeply.

I’m a recovering alcoholic and I long mistook whisky for the holy. After some years of sobriety, I was at my weekly A.A. meeting and a woman said, “I think my drinking was a misguided attempt at a spiritual experience,” and I was floored. What she said made perfect sense to me and I knew it had been true for me, too.

Many years ago, I worked at a liquor store, which is rather obviously a bad place for an alcoholic to work. But I did anyway. I was often scheduled for the opening shift, and so I was the one to unlock the doors and wait on the first customers of the day. We had a regular customer who was always the first in the door on each of the six days a week that we were open. And he always bought the same thing, a 750 of Philips Vodka. (On Saturdays, he’d buy a larger bottle because liquor stores are closed on Sundays in Minnesota and he had to plan ahead.)

He always paid with a check, always the same amount. And I always made him follow the stupid store policy and write his phone number on the memo line, even though his checks never bounced, and he had the same phone number as the day before. I was consistently, passively, and pointlessly mean to him because he disgusted me. I wanted to make it just a little harder for him because I disliked him so much: I was repelled by his chalky, too-pale skin, his red eyes, his sloppy yet robotic movements, his shaking hands. He always wanted a slim paper bag to put his bottle in, and I never offered it – I always made him ask. I hated that he was trying to hide his alcoholism. I wanted to world to know and I wanted him to feel ashamed.

When I remember this now, I am embarrassed by my ignorance, my unawareness, my casual cruelty. I know now that he was a man in the grip of a deep addiction who had terrific suffering. He wasn’t living, he was dying.

I know this because I had the same illness that he did, but I didn’t know it yet. He was my future, and a few short months after I lost that exact job I, too, was asking for my bottles in paper bags and paying for them with poorly written checks. The only difference was that my checks often bounced, and his never did.

When I replay this memory, my heart gets heavy and slow. I feel ashamed and I want to hate my past self. How easy that would be. But I don’t, at least not when I’m at my best. Hating my past self helps nothing and changes nothing. What does help is to understand who I was, what I felt, and why I did what I did. The truth is, I was scared of him. Underneath my self-satisfied disgust, I was scared of him, his world, his obvious suffering. So, I made an unconscious and almost immediate choice to cover that fear with anger, with revulsion. I chose not to feel his suffering because I imagined that it wasn’t mine. I imagined that his life and my life were not connected. I imagined that we were separate. I was wrong.

My practice now is to see my mistake and understand why I did what I did. I see, then accept, then forgive my own unconsciousness, my own fear. I explore and feel fully. My old self doesn’t need to be blamed, shamed, or punished any more than that man did. That doesn’t help. It makes it worse.

My practice now is to let my heart break for who I was and hold that pain in my own loving awareness. I am the holder, and I am the held. This is healing for me.

My practice now is to let my heart break for him, that lost shell of a human, that being who was in such tremendous pain that the hazy gray oblivion of drunkenness was the only bearable way forward.

This is healing for my relationship with what I imagine to be “other.” My practice now is to go back and feel what I felt: my anger, and under it, my fear, to let my heart break for myself and hold myself while it happens.

When we arrive at the honest and undiluted awareness of others’ suffering, compassion awakens naturally in us. Compassion is a very fashionable word these days in spiritual circles, but it’s largely misunderstood. The awakening of real compassion can burn like fire. We usually think compassion is a nice, gooey, Mother Teresa emotion, but it’s not. Compassion is literally “to suffer with,” and it can hurt terribly. Do it anyway. It’s your own life you’re feeling. Don’t turn it off.

If you knew you were dying of cancer and someone said they could heal you with a glass of magic elixir that tasted terrible, you’d drink it. Despite the taste, you want to survive and be whole, so you’d drink it.

In terms of this metaphor, we are all dying of cancer.

If you want to live, practice compassion.

Drink it.

Originally published in the November 2020 Vol. 29.4 issue of Connections.

Busshõ Lahn

Rev. Busshõ Lahn first came to Soto Zen Buddhism in 1993, was ordained as a novice in 2009, and received Dharma Transmission (authorization to carry the lineage and teach independently) in 2015. He is a teacher, speaker, retreat leader, and spiritual director serving the Flying Cloud Zen Contemplative Spiritual Practice Community as well as the Minnesota Zen Meditation Center, Aslan Institute, and the Episcopal House of Prayer. Bussho’s teaching focuses on contemplative spirituality, 12-Step work, interfaith dialogue, and marrying spirituality with both Western and Buddhist psychology. This piece is a chapter from his upcoming book.

Spiritual Companionship and Singing Bowls

By Stacy Montaigne AuCoin, LCSW

Piercing and cradling, the singing bowls’ tones travel in arcs that swell and diminish, resounding within us. They carry us along the arc into inner stillness, along a wavelength, stretching time, and us, toward the eternal. Another tone rises sweetly from the silence, and still another rises and blends. Somehow, our heart responds, and we move our awareness into the moment, merging with the sounds and feeling the resonance within our own bodies and hearts. Each wave of sound dances and harmonizes, at times slight dissonances well up and resolve. Varied tempos and blended notes build and diminish. We feel embraced, filled, present, focused. We feel lighter. We are still. We open.

We hear an inner voice that is often stifled in the loudness of our busy culture. We experience the power of receptiveness and listening deeply. We create space to invite the divine, the eternal, the deep, into our consciousness. We become more conscious of the value, the necessity of receptivity, of listening.

The feel of working with sound and the singing bowls is like no other mode when I work with people in spiritual companionship within my Montana-based practice, and our personal and spiritual development retreats. Almost immediately sound can deepen connection within ourselves, and strip away the superficial and self-conscious. The pure sounds of the singing bowls help us unhook and detach from bombarding noise, drama, doubt, schedules, worries that we encounter daily. In the waves of sound, we flow beyond the confines of ego and “body as self” perspective. The journey with sound gives us a dynamic model of flow that we naturally respond to without getting into our heads. It’s as if the density of our body-self lessens and we become more wavelike, recognizing and experiencing our spiritual selves.

In effect, we make the invisible felt, conscious, palpable. Our experience of the sound opens an alive connection with the divinity within us. It dissolves barriers and walls that separate. We are held and hold each other in the experience of love. And this is the highest form of companioning there is.

With the singing bowls, people are often led to a place where they feel deeply touched. Sometimes people will spontaneously cry and release tension and emotion that was bottled up inside. They report feeling “held” or “enveloped.” Sometimes images emerge for folks as in dreamtime, and we get to explore them together to find insights, guidance, and understanding in their lives. In this work after playing the singing bowls, we make these experiences more conscious through discussions and through listening and being truly present with people. In groups people feel more willing to connect with one another. Once in this zone of deeper awareness, I also encourage expressing and exploring creatively through painting, drawing, writing—to further cultivate a relationship with spirit.

In many ways, I’ve come to understand that I can really feel the Presence moving through the sound of the bowls and through me, and the folks I work with. We hear the sounds externally and simultaneously feel the vibration within our bodies. It is an experience that challenges our feeling of separateness. We can move more easily into the wisdom of spirit.

Finally, I wish to touch upon the importance of intention, holding space, becoming a sacred vessel or conduit in realizing the divine within us. For me personally, it is an essential element for how I approach playing the singing bowls. I particularly want to recognize the palpable loving presence of my life partner and retreat partner, David Summerfield. He holds within him a clarity of knowing that prepares the spaces of our retreats and meditations. I am truly grateful to him for teaching me, for helping me understand more consciously a particular and powerful manner of “holding space.”

Originally published in the May 2019 Vol. 28.2 issue of Connections.

Stacy Montaigne AuCoin, LCSW

Stacy Montaigne AuCoin, LCSW, has a private counseling practice in Bozeman, Montana. A workshop presenter at this year’s SDI Conference in Bellevue, she is also the author of the book, Communication Styles and Therapy with Wind River Native Americans. She leads personal and spiritual development and meditation retreats, and weekly singing bowl meditation gatherings. Stacy earned her master’s degree in clinical social work in 1995 from Smith College, Northampton, MA, and she is licensed in Montana and Wyoming. Stacy and her partner David Summerfield can also be heard discussing the singing bowl as a tool for receptivity and companioning on our SDI Encounters podcast.

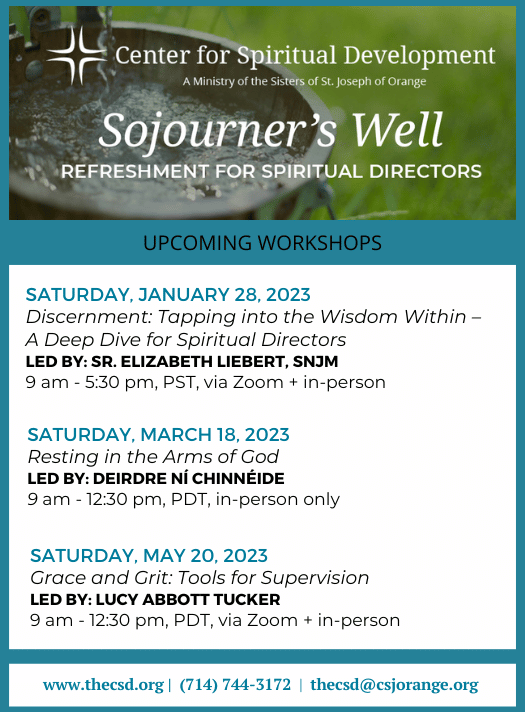

Our Sponsors

Facing Performance Anxiety in Spiritual Direction

By Carrie Myers

It happened more than a year into our relationship as spiritual director and directee. We’d become friends. We had a well-established rhythm: Meet at a coffee shop, chat for a few minutes before moving into “serious” business, end with prayer. We were both comfortable. So why was it at this point that I began feeling anxiety, convinced that everything I said and did was wrong and that each time we met my directee walked away unsatisfied?

Looking back, I think I can trace my fears to two related factors: One, I was finishing up my spiritual direction training program. I was about to become a fully- fledged, licensed spiritual director. I should have known what I was doing by then, right? The grace period was almost over. But the second, more consequential factor was this: My directee had begun paying me.

I had started seeing my directee—I’ll call her Naomi— right at the beginning of my training program. She was one of my first guinea pigs, the first “patient” in my “residency,” although neither metaphor really captures the dynamic of a spiritual companionship. Naomi was giving me her time and trust and I was giving her my best efforts at direction. It was an even exchange. But now that Naomi had decided she wanted to pay me (she did this on her own behest, without me bringing it up), all of a sudden, I felt an asymmetry in the relationship. I was working for her now and I had to deliver the goods. I found myself distressed, distracted, and convinced I was failing at every turn. That Naomi was going through a rough period in her prayer life only exacerbated things, because I felt I was hindering rather than helping her. After two of these seemingly disastrous meetings, I was a mess.

When my training cohort met next, I asked my fellow students and peer supervisors for help processing my fears. Through gentle questioning and probing, they helped me arrive at a few insights: First, I am a high-performing perfectionist with a low tolerance for my own mistakes and an inferiority complex when it comes to work. Once meeting with my directee began to feel like “work” rather than “training,” that inferiority complex kicked in with a vengeance. As much as I thought I had grown in that area, I obviously had a ways to go. Second, I realized that when I am in the sacred space of spiritual direction, I may need to be aware of other supernatural presences besides God’s. My faith tradition tells me that we have an enemy who will “steal, kill, and destroy” (John 1:10) in any way he can, from us and from those we walk with on their spiritual journeys, and I came to believe that enemy was trying to take away from the joy that I feel as a spiritual director by preying on my vulnerabilities.

So, what have I taken away from this experience of dealing with spiritual direction performance anxiety?

The need for supervision.

- The gift of wise and listening colleagues.

- A heightened sense of the stakes of my work in the presence of evil as well as goodness.

- And finally, a renewed awareness of my need to trust the God who guides all my interactions and whose desire for my directee’s good far outweighs my own.

As I continue to work with Naomi, my prayer is for God to grow us both in what Ignatius calls spiritual freedom: “living the gifts—each and all of the gifts—that God gives us” while continually moving towards greater hope, joy, peace, and love.

Originally published in the March 2018 Vol. 27.2 issue of Connections.

Carrie Myers

Carrie Myers is a fledgling spiritual director finishing up her training at the School of Sustainable Faith. She is also a writer, poet, educator, and worship musician. She is married to Ryan, with whom she has three children (and a guinea pig) and leads Vineyard One NYC, a diverse church community in Brooklyn. Carrie has a PhD in English and American Literature from New York University and has taught at institutions including NYU, Barnard College, and City Seminary of New York. She blogs about family, faith, and spiritual direction at “Ravished by Light” (https://www.carriemyers.blog/). She is a member of SDI.

The Spirituality of a Prison Labyrinth

By Lorraine Villemaire, MA,SSJ; Catherine Rigali, LPN; Donna Zucker, PhD, RN, FAAN; and Kathryn Callahan, MS, RN

The popularity of labyrinths over the last few years goes beyond anyone’s expectation. The phenomenon reflects not only the spiritual hunger that exists in our world, but a hunger most prevalent in the chaotic atmosphere of a prison.

The United Sates has 2.4 million people behind bars. Over 50% return to correctional facilities within three years. To lessen these statistics, educational and treatment programs place an emphasis on helping inmates re-integrate themselves into a life without recidivism, gain dignity, and become productive members of society.

A labyrinth program is a creative way to help reach this goal. It allows inmates time to reflect on the past, be in the present moment, and ponder a better future. Many inmates realize that in order to succeed, they must learn to find and relate to the higher Spirit who dwells within. The labyrinth is the spiritual tool that enables the inner and outer worlds to come together. Walking a labyrinth changes the thought process that may impact actions and behaviors. The experience offers new skills to use as a lifeline.

An important goal of the labyrinth walk is to be aware of the message the body wishes to convey. The body often gives a message the mind cannot give. By taking deep breaths and relaxing the body, a message or feeling usually surfaces. Being with and sharing this feeling with Higher Spirit offers guidance in life situations.

The twelve-week labyrinth program in the Hampshire Jail and House of Correction in Northampton, Massachusetts, USA, consists of the following themes: Introduction to the labyrinth, relaxation, self- esteem, positive thinking, forgiveness, peace, moral development, problem solving, meditation, laughter, spirituality, and prayer. Each class begins with relaxation exercises, input on the theme, the walk, and processing the experience through journal writing or oral discussion. The program is now in its eighth year.

Three years after the program started, an anonymous donor gave funds to build an in-ground labyrinth within the high, razor fences; the first in-ground labyrinth in a correctional facility in the United States. The full story of the process can be seen on YouTube under the title, Pathway to Change: The Jail Labyrinth Project.

What better place to bring a labyrinth than a jail. There is no greater satisfaction than witnessing the effect of a labyrinth walk on inmates. Consider their words:

“I don’t feel like I’m in jail when I walk the labyrinth.”

“I am closer to God and my faith.”

“I learned how to direct my anger by breathing and to take a step back and look at a situation in another way.”

“I think I can look at a negative situation and use the tools I learned to be a positive role model.”

“I understand more peaceful ways to resolve my problems.”

“When I walk the labyrinth I can forgive myself.”

Prisons are stressful places to live. They are noisy and crowded. For those who desire to engage the labyrinth, it is a source of light, hope, and opportunity for rehabilitation and change.

Originally published in the May 2015 Vol. 24.1 issue of Connections.

Would you like to learn more? Spiritual Directors International members Rev. Dr. Melanie L. Harris and Rev. Dr. Naomi O. Harris describe how they incorporate the labyrinth in their contemplative practice and demonstrate ways to include the labyrinth and other forms of walking meditation in spiritual direction. As African American women, they speak to the value of spiritual direction and the labyrinth for people of color. Increasingly, the availability of the labyrinth in hospitals, hospice settings, prisons, city parks, community centers, neighborhood backyards as well as retreat centers, churches, and temples encourage every day encounters with the sacred. Are you called to offer spiritual direction including the labyrinth? Learn more on the SDI YouTube channel.

Publisher: Spiritual Directors International

Executive Director: Rev. SeiFu Anil Singh-Molares

Editor: Phil Fox Rose

Production Supervisor: Ann Lancaster

Submissions: [email protected]

Advertising: [email protected]

Connections is published four times a year. The names Spiritual Directors International™, SDIWorld™, and SDI™ and its logo are trademarks of Spiritual Directors International, Inc., all rights reserved. Opinions and programs represented in this publication are of the authors and advertisers and may not represent the opinions of Spiritual Directors International, the Coordinating Council, or the editors.

We welcome your feedback on any aspect of this issue of Connections, or on SDI as a whole. Please send your comments to [email protected].

The Home of Spiritual Companionship

PO Box 3584

Bellevue, WA 98009